Bayesian Inference

3.2. Bayesian Inference¶

We already discussed Bayes’ theorem as well as Bayesian inference using the example of a coin toss in the previous section. In the present section, we present Bayesian inference in a more formal way in order to be able to apply the general concept later on to machine learning models.

The following setting is assumed:

Some data \(\mathcal{D}\) is given. For example, this data contains the outcomes of coin tosses. \(\mathcal{D}\) can also contain multiple input-output pairs \((x_i, y_i)\) which are related by some function \(f\) (i.e., \(y_i = f(x_i)\)). This situation is of particular importance in supervised machine learning.

\(x\) denotes a general data point

A parameter \(\theta\) (possibly vector valued) specifies the distribution of the data. For example, \(\theta\) is the parameter of the Bernoulli distribution in the coin toss example.

In order to perform Bayesian inference, the following steps are necessary:

Assign a prior distribution to \(\theta\). This distribution can again depend on some so-called hyperparameters. In the coin toss example, we used the beta distribution \(\text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\), i.e., \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the hyperparameters.

Use Bayes’ theorem and the data \(\mathcal{D}\) in order to caluclate the posterior distribution of \(\theta\):

\[p(\theta~|~\mathcal{D}) = \frac{p(\mathcal{D}~|~\theta)~p(\theta)}{p(\mathcal{D})}\]\(p(\theta~|~\mathcal{D})\) denotes the posterior distribution

\(p(\mathcal{D}~|~\theta)\) is the likelihood

\(p(\theta)\) is the prior distribution

\(p(\mathcal{D})\) is called the marginal likelihood or evidence and is given by

\[p(\mathcal{D}) = \int p(\mathcal{D}~|~\theta)~p(\theta)~d\theta\]

In the coin toss example, it turned out that the posterior distribution is again a beta distribution. Thus, the prior was chosen such that its combination with the likelihood in Bayes’ theorem yields a posterior which is from the same family of probability distributions. As mentioned before, this kind of prior is called conjugate prior. A table of conjugate priors for many likelihoods can be found on Wikipedia.

The prior as well as the positrior distribution can be used to make probabilistic predicitions about the distribution of new data points. The prior predictive distribution is given by

and the posterior predictive distribution by

For example, in the coin toss example we can calulate the probability for heads in the next experiment. The use of the prior predictive distribution means that we only include our prior beliefs on \(\theta\) which was given by the \(\text{Beta}(2, 2)\) distribution. Recall that the likelihood is \(\text{B}(1, \theta)\)-distributed and therefore, \(p(H~|~\theta) = \theta\), where \(H\) denotes the elementary event “heads”. Thus, it follows

The probability for heads equals in this case the expectation of the prior distribution which is \(0.5\) in this example. Here, we used that the expectation of \(\text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta)\) is \(\alpha/(\alpha + \beta)\).

The posterior predictive distribution uses the posterior distribution of \(\theta\) and hence, also the data \(\mathcal{D}\). Assume that we tossed the coin five times and observed 3 heads and 2 tails. In the previous section, we have seen that \(\text{Beta}(2 + 3, 2 + 2) = \text{Beta}(5, 4)\) is the posterior distribtion. Similarly as before,

is exactly the expectation of the posterior distribution which equals \(5/9\).

Hence, by observing more heads than tails our belief tend to expect heads more likely than before.

Depending on the choice of the prior distribution and the distributional form of the likelihood, it can be very demanding to caluclate the marginal likelihood

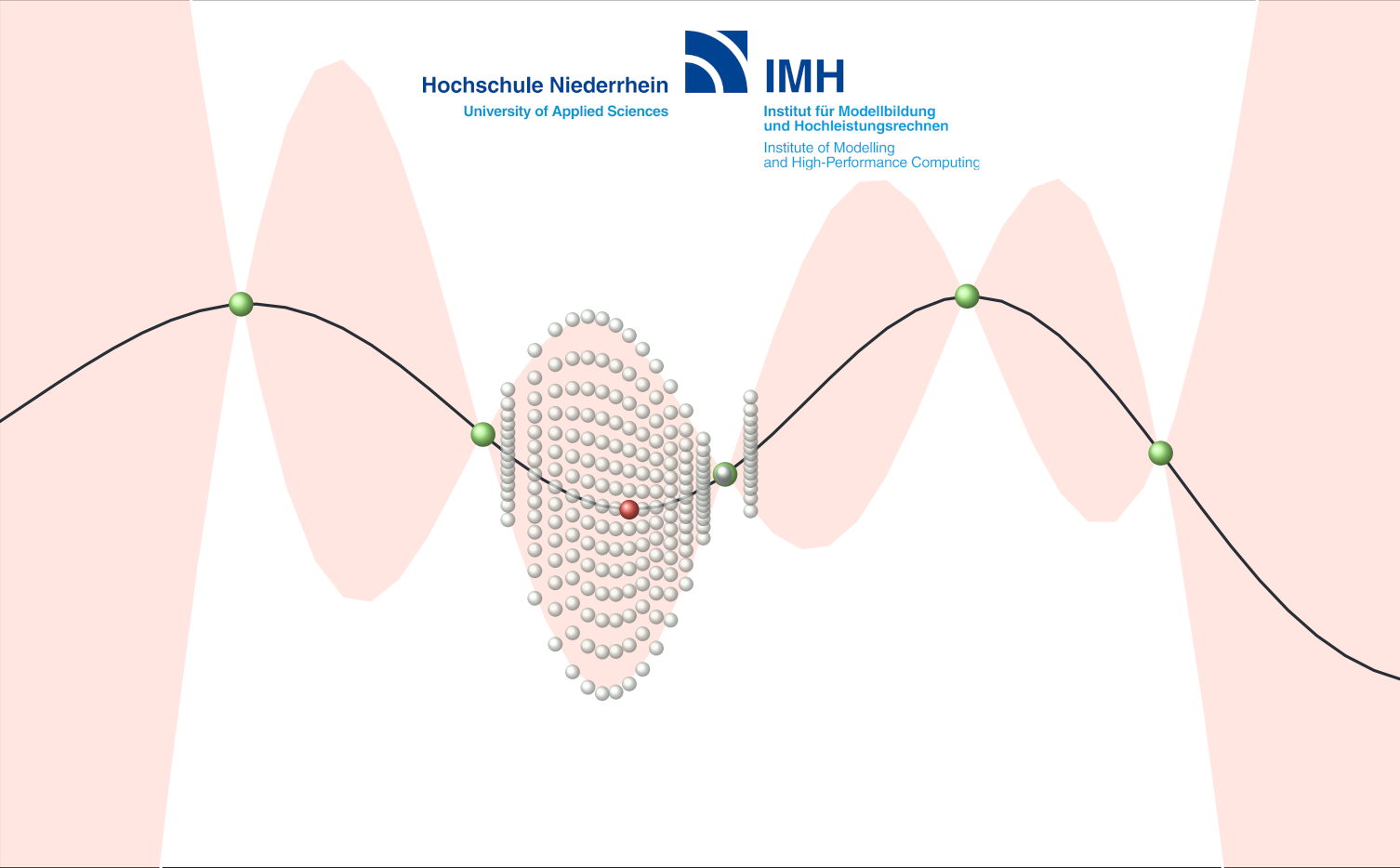

In particular, in high dimensions this term can become intractable. In this case, the posterior distribution can not be caluclated expicitly, but some approximation techniques can be used. Very common are Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods or variational inference (refer to chapters 21 to 24 in [1]). Nevertheless, these methods are out of the scope of this lecture. Instead, it is also possible to simplify the problem and not to compute the complete posterior distribution. This will be discussed in the following section.

- 1

K. P. Murphy. Machine learning : A Probabilistic Perspective. MIT Press, 2012.