Linear Regression

Contents

3.4. Linear Regression¶

In this section, we illustrate the preceding concepts for the case of a linear regression model. The probabilistic concepts are applied to the linear setting and the connection to classical (deterministic) methods are shown.

We assume the following setting:

Some data of the form

\[\mathcal{D} = \{ (x_i, y_i)~|~x_i, y_i \in \mathbb{R} \quad \text{for } i = 1,\dots, n\}\]is given

The data \(\mathcal{D}\) is collected from observation with the relation

\[y_i = \beta~x_i + \varepsilon_i,\]where \(\beta \in \mathbb{R}\) and \(\varepsilon_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_{\text{noise}}^2)\), \(i=1, \dots, n\) are independent normally distributed random variables. For simplicity, we suppose that \(\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2\) is known.

\(\varepsilon_i\) represents some error term (e.g. measurement errors) which is also called noise. The unknown coefficient \(\beta\) is called slope. Please note that the outputs \(y_i\), \(i=1,\dots,n\), are also independent normally distributed random variables with distribution \(\mathcal{N}(\beta~x_i, \sigma_{\text{noise}}^2)\). \(x\) and \(y\) denote vectors containing all \(x_i\) and \(y_i\), \(i=1,\dots,n\), respectively.

Our goal is to use the information in \(\mathcal{D}\) to estimate \(\beta\) in an appropiate way. In use of these estimates, it is possible to make predictions for new inputs \(x^*\). Similarly, the probabilistic concepts are applied later on to more advanced models.

For the purpose of visualization, we generate a linear function as well as some samples:

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import uniform, norm, laplace

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# set seed

np.random.seed(seed=3141592)

# generate true value of beta randomly

# in use of a standard normal distribution

beta = norm.rvs(loc=0, scale=1)

interval_length = 1 # lenght of the interval around 0 for x values

boundary = np.array([-interval_length/2, interval_length/2]) # auxiliary array for plots

n = 10 # number of observations

sigma2 = 0.05 # noise level

# generate data

x = interval_length * uniform.rvs(size=n) - interval_length/2 # x values

y = beta * x + norm.rvs(loc=0, scale=np.sqrt(sigma2), size=n) # y values

print("beta = {:1.4f}".format(beta))

beta = -0.4955

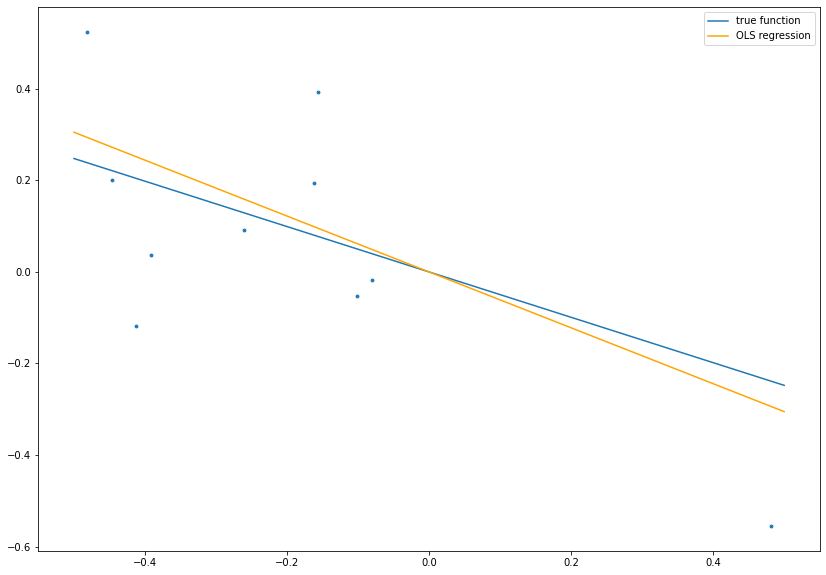

3.4.1. Ordinary Least Squares¶

The most common approach is to choose an estimate \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{OLS}}\) for \(\beta\) such that the sum of squared resiudals (SSR) (or residual sum of squares (RSS)) between observations and predictions is minimized, i.e.,

The solution is given by

In our probabilistic setting, the same result is obtained by the MLE estimate. Since the observations \(y_i\), \(i=1,\dots,n\), are independent and \(\mathcal{N}(\beta~x_i, \sigma_{\text{noise}}^2)\)-distributed, the joint probability density function of \(y\) reads

Thus, the MLE yields

Since \(\ln\) is a monotonically increasing function, we can apply it to the righthand side without changing the \(\text{argmax}\). Consequently, it holds

i.e., the MLE estimate minimizes the SSR and \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{MLE}} = \hat{\beta}^{\text{OLS}}\).

# calculate OLS estimate

betaOLS = np.dot(x, y)/np.dot(x, x)

# plot data, true function and OLS result

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

plt.scatter(x ,y, s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, label='true function')

plt.plot(boundary, betaOLS*boundary, c='orange', label='OLS regression')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

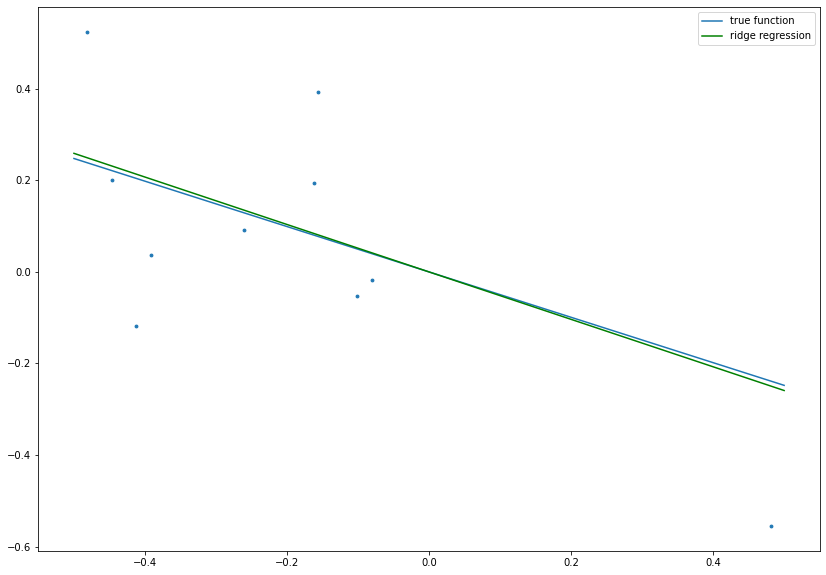

3.4.2. Ridge Regression¶

Instead of minimizing the sum of squared resiudals, it is in some cases useful to introduce an additional regularization term. The use of a so-called \(L^2\)-regularization leads to ridge regression. In this case, the approach is to choose \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Ridge}}\) such that

The regularization term penalizes large values of the slope \(\beta\). This means that a steep regression line is not desired. The parameter \(\lambda > 0\) is called complexity parameter and controls how much influence the regularization has.

Again, the solution can be calculated explicitly and is given by

In our probabilistic setting, the same result is obtained by the MAP estimate with Gaussian prior. We assume that \(\beta \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_{\beta}^2)\). This choice expresses the expectation that \(\beta\) should probably be close to zero. The variance \(\sigma_{\beta}^2\) is a hyperparameter and is the counterpart to the complexity parameter \(\lambda\). The MAP estimate \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Gauss}}\) is given by

Please note that \(p(\mathcal{D}~|~\beta)~p(\beta)\) is (up to normalization) again a normal distribution. Similarly to the MLE case, by dropping constants and application of \(\ln\) the estimate can be rewritten as

Thus, \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Gauss}} = \hat{\beta}^{\text{Ridge}}\) with \(\lambda = \frac{\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2}{\sigma_{\beta}^2}\).

# set complexity parameter for ridge regression

lambdaRidge = 0.2

# calculate ridge regression estimate

betaRidge = np.dot(x, y)/(np.dot(x, x) + lambdaRidge)

# plot data, true function and ridge regression result

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

plt.scatter(x ,y, s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, label='true function')

plt.plot(boundary, betaRidge*boundary, c='g', label='ridge regression')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

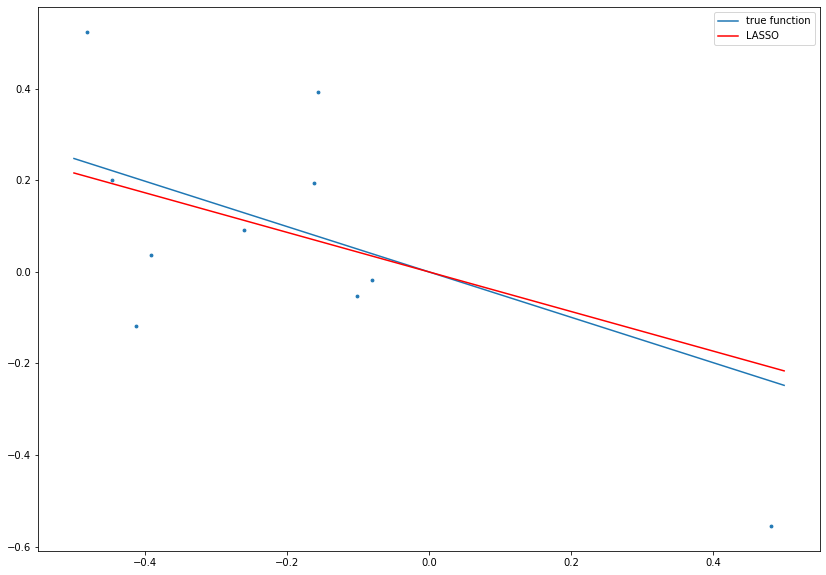

3.4.3. LASSO¶

LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) is a regression method that is similar to ridge regression, but usses \(L^1\)-regularization instead of \(L^2\)-regularization, i.e., the approach is to choose \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{LASSO}}\) such that

The \(L^1\)-regularization term also penalizes large values of the slope \(\beta\), but it is even stronger than \(L^2\)-regularization for \(\lvert \beta \rvert < 1\), since \(\lvert \beta \rvert > \beta^2\).

Again, the solution can be calculated explicitly and is given by

where \(\text{sgn}\) denotes the sign function (i.e., \(\text{sgn}(x) = 1\) if \(x \ge 0\) and \(\text{sgn}(x) = -1\) if \(x < 0\)). In particular, \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{LASSO}} = 0\) if the absolute value of \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{OLS}}\) is too small.

In our probabilistic setting, the same result is obtained by the MAP estimate with Laplace prior. We assume that \(\beta \sim \text{Laplace}(0, b)\). Similarly to the Gaussian prior, this choice expresses the expectation that \(\beta\) should probably be close to zero, but this distribution is sharper at zero. The MAP estimate \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Laplace}}\) is given by

Similarly as before, by dropping constants and application of \(\ln\) the estimate can be rewritten as

Thus, \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Laplace}} = \hat{\beta}^{\text{LASSO}}\) with \(\lambda = \frac{2\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2}{b}\).

# set complexity parameter for LASSO

lambdaLASSO = 0.1

# calculate LASSO estimate

betaLASSO = np.sign(betaOLS) * np.maximum(0, np.abs(betaOLS) - 2*lambdaLASSO/np.dot(x, x))

# plot data, true function and LASSO result

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

plt.scatter(x ,y, s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, label='true function')

plt.plot(boundary, betaLASSO*boundary, c='r', label='LASSO')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

OLS, ridge regression and LASSO can also be generalized to higher dimensions, i.e., instead of scalar values for \(x\) and \(\beta\) \(d\)-dimensional vectors can be considered. In particular, in this more general setting LASSO is used to discard input variables, since the regularization yields \(\beta_j = 0\) if the \(j\)-th variables does not seem to have an impact on \(y\).

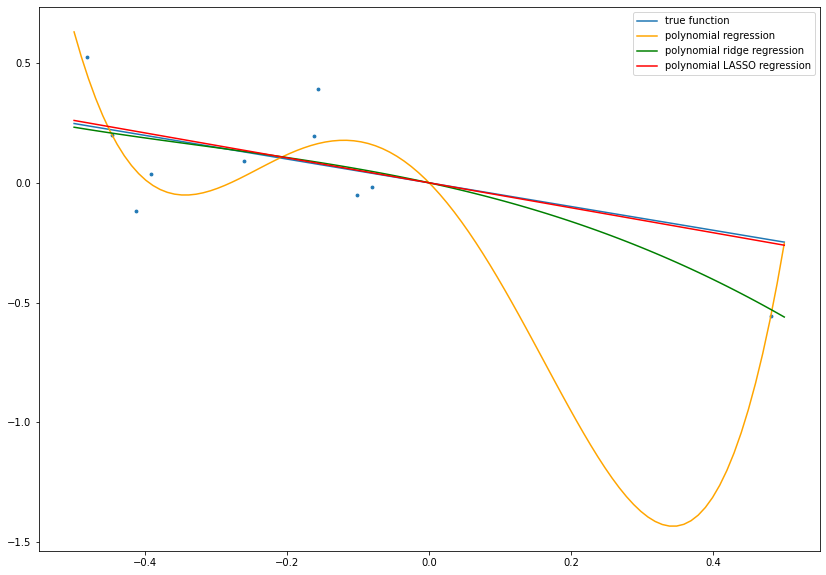

3.4.4. Regularization and Overfitting¶

In application, the regularization techniques such as \(L^2\)-regularization in Ridge Regression and \(L^1\)-regularization in LASSO are usually used to prevent overfitting. As before, we use data with the linear relation

In most cases, the exact relation is unknown, since we only observe the data \(\mathcal{D}\). Thus, we could also try to fit a more complex model to the data, e.g., a polynomial model of the form

The parameters \(\beta_1\), \(\beta_2\), \(\beta_3\) and \(\beta_4\) can be optimized similarly as before by minimizing the RSS without or with regularization. Since the true relation is linear, the polynomial model without regularization is too complex and will result in overfitting (i.e., the model adapts too strong to the given data and generalizes bad to unseen data), whereas the regularized versions yield a more realistic model:

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression, Ridge, Lasso

# add features x**2, ..., x**4

poly = PolynomialFeatures(4, include_bias=False)

x_poly = poly.fit_transform(x.reshape(-1, 1))

# fit linear model without regularization

linregr = LinearRegression(fit_intercept=False)

linregr.fit(x_poly, y)

# fit ridge regression model

ridge = Ridge(alpha=1e-2, fit_intercept=False)

ridge.fit(x_poly, y)

# fit LASSO model

lasso = Lasso(alpha=1e-2, fit_intercept=False)

_ = lasso.fit(x_poly, y)

# plot data, true function and results

x_plot = np.linspace(-interval_length/2, interval_length/2, num=100)

x_plot = poly.transform(x_plot.reshape(-1, 1))

y_linregr = linregr.predict(x_plot)

y_ridge = ridge.predict(x_plot)

y_lasso = lasso.predict(x_plot)

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

plt.scatter(x ,y, s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, label='true function')

plt.plot(x_plot[:, 0], y_linregr, c='orange', label='polynomial regression')

plt.plot(x_plot[:, 0], y_ridge, c='green', label='polynomial ridge regression')

plt.plot(x_plot[:, 0], y_lasso, c='red', label='polynomial LASSO regression')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

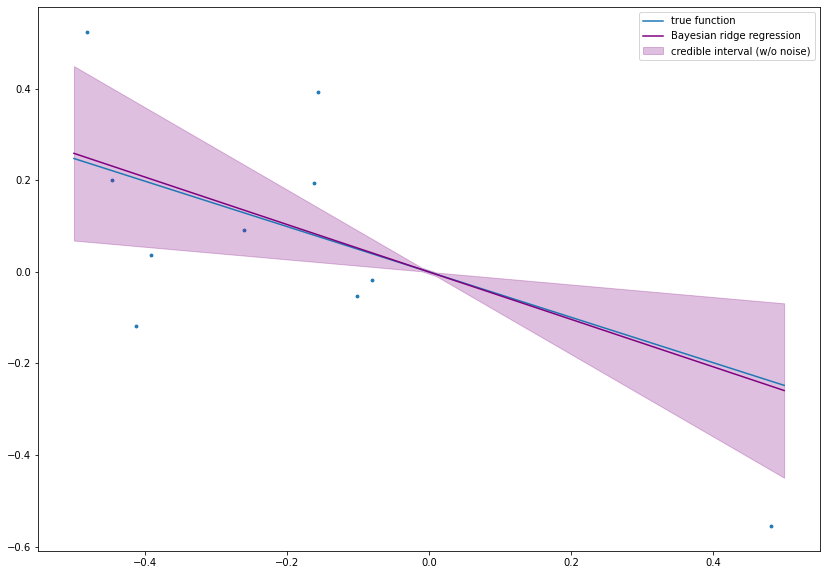

3.4.5. Bayesian Ridge Regression¶

In the ridge regression section, we have already mentioned that the use of a Gaussian prior \(\mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_{\beta}^2)\) for \(\beta\) results in a Gaussian posterior. In other words, the Gaussian distribution is its own conjugate prior.

In order to obtain the posterior distribution, it remains to determine its mean and variance. In detail, it holds

where \(\Lambda := x^Tx + \frac{\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2}{\sigma_{\beta}^2}\). Thus, \(\mathcal{N}(\tilde{\mu}, \tilde{\sigma}^2)\) is the posterior distribution with mean

and variance

Please note that the mean \(\tilde{\mu}\) equals the MAP estimate \(\hat{\beta}^{\text{Gauss}}\) which is used in ridge regression.

Bayesian ridge regression has the nice property that the prediction \(y^* = \beta~x^*\) for a test point \(x^* \in \mathbb{R}\) is again normally distributed, since \(\beta \sim \mathcal{N}(\tilde{\mu}, \tilde{\sigma}^2)\), i.e., \(y^* \sim \mathcal{N}(x^* ~ \tilde{\mu}, (x^*)^2~\tilde{\sigma}^2)\). In particular, credible bounds for \(y^*\) can be computed. Additionally to the expected value of the output, the model is also able to quantify its own uncertainty! This is a huge advantage and a major reason to use probabilistic models. Furthermore, it is also useful to consider the additional noise term which leads to the distribution of \(\beta~x^* + \varepsilon^*\) with \(\varepsilon^* \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_{\text{noise}}^2)\). The noise is assumed to be independent of \(\beta\) and therefore, it follows

\((x^*)^2~\tilde{\sigma}^2\) is also called epistemic uncertainty (caused by lack of knowledge of the model) and \(\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2\) is called aleatoric uncertainty (caused by the noise which can not be reduced by an improved model).

# choose prior variance such that posterior mean equals betaRidge

sigma2_beta = sigma2/lambdaRidge # prior variance

posterior_mean = np.dot(x, y)/(np.dot(x, x) + sigma2/sigma2_beta)

posterior_var = sigma2 / (np.dot(x, x) + sigma2/sigma2_beta)

# calculate mean predictions and variances on testpoints

xstar = np.linspace(-interval_length/2, interval_length/2, num=50)

ystar_mean = posterior_mean * xstar

ystar_var = posterior_var * np.square(xstar)

# plot data, true function and Bayesian linear regression result

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

plt.scatter(x ,y, s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, label='true function')

plt.plot(xstar, ystar_mean, c='purple', label='Bayesian ridge regression')

plt.fill_between(xstar, ystar_mean - 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var), ystar_mean + 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var),

color='purple', alpha=.25, label='credible interval (w/o noise)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

In the case that the variance \(\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2\) of the noise term is not known, it is also possible to perform Bayesian inference on \(\beta\) and \(\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2\) simultaneously. In this case, the inverse gamma distribution would be used as prior distribution for \(\sigma_{\text{noise}}^2\).

3.4.6. Visualization¶

To visualize and to compare the preceding models for different parameter values please open the notebook in Google Colab and use the application below.

from IPython.display import display, clear_output

!pip install ipympl

clear_output()

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import uniform, norm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ipywidgets import interact, interact_manual, IntSlider, FloatSlider

import ipywidgets as widgets

# function to # generate data of linear function

def generate(interval_length, n):

np.random.seed()

beta = norm.rvs(loc=0, scale=1)

x = interval_length * uniform.rvs(size=n) - interval_length/2 # x values

return beta, x

style = {'description_width': 'initial'}

il_w = IntSlider(value=1, min=1, max=10, description='interval length', continuous_update=False, style=style)

n_w = IntSlider(value=10, min=5, max=40, description='n', continuous_update=False)

estimates_w = widgets.SelectMultiple(

options=['OLS', 'Ridge', 'LASSO', 'Bayesian'],

value=['OLS', 'Ridge', 'LASSO'],

description='estimates')

noise_w = widgets.Checkbox(value=False, description='with noise')

# auxiliary function for plots

def _plot(interval_length, beta, x, y, estimates, noise, sigma2_noise,

betaOLS, betaRidge, betaLASSO,

posterior_mean, posterior_var):

# calculate mean predictions and variances on testpoints

xstar = np.linspace(-interval_length/2, interval_length/2, num=50)

ystar_mean = posterior_mean * xstar

ystar_var = posterior_var * np.square(xstar)

# get plot

boundary = np.array([-interval_length/2, interval_length/2])

fig= plt.figure(figsize=(14, 10))

fig.canvas.header_visible = False

plt.scatter(x ,y, color='b', s=8.)

plt.plot(boundary, beta*boundary, c='b', label='true function')

if 'OLS' in estimates:

plt.plot(boundary, betaOLS*boundary, c='orange', label='OLS')

if 'Ridge' in estimates:

plt.plot(boundary, betaRidge*boundary, c='g', label='ridge regression')

if 'LASSO' in estimates:

plt.plot(boundary, betaLASSO*boundary, c='r', label='LASSO')

if 'Bayesian' in estimates:

plt.plot(xstar, ystar_mean, c='purple', label='Bayesian ridge regression')

if noise:

plt.fill_between(xstar,

ystar_mean - 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var + sigma2_noise),

ystar_mean + 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var + sigma2_noise),

color='purple',

alpha=.25, label='credible interval (w noise)')

else:

plt.fill_between(xstar,

ystar_mean - 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var),

ystar_mean + 1.96 * np.sqrt(ystar_var),

color='purple',

alpha=.25, label='credible interval (w/o noise)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

@interact(interval_length=il_w,

n=n_w)

def lin_func(interval_length, n):

# generate linear function and data

beta, x = generate(interval_length, n)

# perform linear regression

@interact(estimates=estimates_w,

noise=noise_w,

sigma2_noise=FloatSlider(value=0.01, min=0.001, max=0.2, step=5e-3,

continuous_update=False, style=style),

lambdaRidge=FloatSlider(value=0.2, min=0., max=1., step=0.01,

continuous_update=False, style=style),

lambdaLASSO=FloatSlider(value=0.1, min=0., max=1., step=0.01,

continuous_update=False, style=style),

sigma2_beta=FloatSlider(value=0.1, min=0., max=0.25, step=0.01,

continuous_update=False, style=style))

def lin_reg(estimates, noise, sigma2_noise, lambdaRidge, lambdaLASSO, sigma2_beta):

np.random.seed(seed=4711)

y = beta * x + norm.rvs(loc=0, scale=np.sqrt(sigma2_noise), size=n) # y values

# calculate OLS, ridge and LASSO estimates

betaOLS = np.dot(x, y)/np.dot(x, x)

betaRidge = np.dot(x, y)/(np.dot(x, x) + lambdaRidge)

betaLASSO = np.sign(betaOLS) * np.maximum(0, np.abs(betaOLS) - 2*lambdaLASSO/np.dot(x, x))

# Bayesian ridge regression

posterior_mean = np.dot(x, y)/(np.dot(x, x) + sigma2_noise/sigma2_beta)

posterior_var = sigma2_noise / (np.dot(x, x) + sigma2_noise/sigma2_beta)

params = (interval_length, beta, x, y, estimates, noise, sigma2_noise,

betaOLS, betaRidge, betaLASSO,

posterior_mean, posterior_var)

# get plot

_plot(*params)